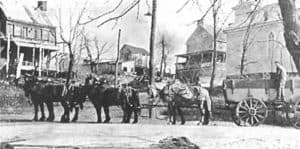

The mill and its race as it appeared early in the 20th century. The additions at the rear of the building have since been removed.

The Old Mill of Waterford

This account is a merging of an article by Ruth Bentley and John E. Divine in a 1982 Waterford Foundation booklet and an excerpt from the book, When Waterford & I Were Young, by John E. Divine. This book shares the author’s experiences and love of Waterford as he grew up in the early 1900s. About this book

More on Waterford's mills »

Waterford Mill—Historic Structure Report »

In 1928, the octogenarian Mary Dutton Steer wrote in her Early Memories of Waterford, "The ever-changing owners of the ever-busy mill." As one examines the records of ownership, the truth of her statement becomes apparent.

Amos Janney settled in the Loudoun Valley in 1733 and soon after built a log mill on Catoctin Creek, not far from the present location of the Old Mill. His son, Mahlon, developed this family mill into a larger operation by 1762, when he erected a larger mill of wood on a stone foundation, at the site of the present mill. Mahlon's new mill was a custom mill, grinding not only wheat grown on his own land but also providing services for other farmers settling around "Janney's Mill."

Excerpt from the book, When Waterford & I Were Young, by John E. Divine

No matter who the mill owner, there was always interesting activity in that end of town. In my time, "Parks and Recreation" was phrase unheard of, so each youngster made his or her entertainment wit what was at hand. Quite often it revolved around the mill. The large wheat and shelled-corn bins offered fun when we could jump from height of several feet to sink into the grain. This could be done only if we managed to sneak by the miller to the upper floors where the bins were. got one of the better beatings of my life one day when I got caught in the bin and then didn't get out quick enough when the miller's assistant told me to leave. Then there was the cob bin, which offered hiding places an. ample 2mmimition for corn cob wars.

There was another use for the corn cobs, incidentally. Sarah Rucker Gordon (1896-1992) remembered it was one of her family jobs as a chit to go to the mill around suppertime, especially in the summer when there might not be a good bank of coals in the cook stove, and buy-for five cents-a large sack of dry cobs for a quick fire start in the stove or to increase the speed of one.

Teams of four or six horses would haul in wheat or corn to be ground into flour or meal. I even saw a yoke of oxen come to the mil one day, the only ones I ever saw in Waterford. Henry Clapham, farmer from near Milltown north of the village, had this team, and it was a sight to see those two oxen go swinging along. [Some historians occasionally refer to "Milltown" as an early name of the village that is now Waterford. I have seen no evidence to persuade me of that. There is, however, a tiny settlement called Milltown about two miles north of Waterford (at the intersection of modern Rts. 681 & 692).]

In my youth a metal-clad frame elevator was attached to the west o creek end of the mill. This also housed a cider mill in the early to mid 1920s where the men pressed cider one day a week in the fall months. A row of horse stables stood about forty feet behind the elevator. In my time, I can remember the miller owned only one four-horse team. But a historian writing of Civil War days recorded that Samuel C. Means [Samuel Carrington Means (1827-1884)], the prosperous miller of that time, had 28 horses at the outbreak of war to haul his products across the Potomac to Point of Rocks for shipment or the B&O Railroad or C&O Canal, and for other mill-related hauling.

Mahlon eventually erected a larger, two-story mill "of wood and of stone" on a near-by site, which he eventually bought from his Uncle Francis in 1762 "with improvements thereon." For more than half a century after the family's arrival the tiny settlement that developed around the structure was known simply as Janney's Mill. Over the years many other mills were built in the area, but the one Waterford now calls simply "the mill" remained the best known.

The Janneys, Amos and son Mahlon, built and ran the first two mills in unbroken line from 1738 until 1808. This represents the longest period in which one family operated the business in the 150 years of its existence. Mahlon Janney leased and then sold his mill to Jonas Potts several years before he died in 1812; ownership changed hands many times after that." It was apparently Thomas Phillips who around 1831 rebuilt Mahlon's mill into the three-story brick structure that stands today.

The Mill Race

The millrace was quite an engineering feat for its 18th-century builders, both in design and construction in diverting water to drive the mill. Adam across the main body of Catoctin Creek started water on its way toward the mill carried by nearly a mile of race.

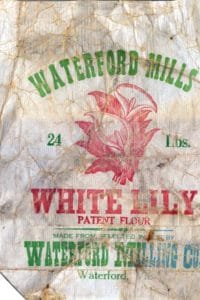

On its course, it picked up waters of Balls Run through a curious contraption called The Chute. This had overhead bridging supporting swinging gates that turned the water of the run at the race junction but also allowed flood waters to push open the swinging gates. Two small lift gates, one between the dam and the chute, and one between the chute and the mill, were used to flush the race of silt. I can remember some nights during a summer thunderstorm seeing the miller or his helper, with lantern in hand, going up the race to lift the gates to release the flood, his lantern bobbing as he rushed to get to each gate.In the mill's later years a gasoline or kerosene engine was added for power so that grinding would not be interrupted in times of drought. The old overshot waterwheel and later turbine were giving way to a more modern way of milling. But the noisy exhaust from the engine never matched the distinctive rhythmic rumble of the big wheel. The romance of water-driven mills was gone and with it waterground meal and Waterford's White Lily flour, that being the trade name of the product that came from the mill.

A Succession of Owners

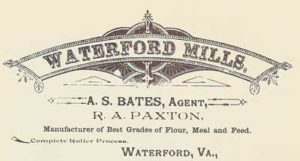

A succession of owners ran the mill through the first half of the nineteenth century. Thomas Phillips built the present building in 1838, but he was an investor, not a miller, and soon sold it. In the late 1850's, Samuel Means operated, then owned, the business. Apparently these were the most productive years for the mill, and Means grew quite prosperous. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Means had six teams on the road hauling his products to market.

During the war, the Confederates drove Means from his home and business, and appropriated all his livestock and goods. Means was ruined, and after the war sold the mill. The mill changed owners a number of times until 1922, when it was bought by William S. Smoot, who operated it until his death in 1936. As Mr. Smoot's health declined he was forced to reduce mill operations. He used only the first two floors, and discontinued tolling operations (in which for every six bushels of wheat the farmer brought in, he received two barrels of flour. The miller kept the rest, to store and sell.) The mill machinery became rusty and the burrs (millstones) dull.

The End of the Mill

Edward Chamberlin, a local resident who was deeply interested in preserving and restoring Waterford, had some years before embarked on a program of buying up abandoned or deteriorating Waterford properties. He was concerned about the decline of the mill operation and the deterioration of the equipment, and after Mr. Smoot's death made arrangements to continue operating the mill.

However, since he knew nothing about the operations of a mill, Mr. Chamberlin enlisted the help of George Babson and Festus Foster to upgrade and supervise. Albert White was employed as salesman and "Shipping Department" and a Mr. Tinsman and his son Tom employed as millers. Soon the mill was producing com meal, flour, bran, and middlings (mixed flour and fine bran) under the name of "Quaker Town Products". Tolling was resumed. Mill products were trucked by Mr. White to markets in Washington and Baltimore. But the expense and bother of keeping the machinery in order, the mill race open, and the bums sharpened, outweighed the profits from sales, and in the fall of 1938 the mill was turned back to the Smoot family. William S. Smoot, Jr., having just returned from college, tried his hand at operating it but soon found himself in the same straits as his predecessors. In April, 1939, he declared bankruptcy and closed the mill for the last time.

The mill had had a long and honorable life as the principal business of the community, but was not kind to many of its owners.In 1943, when the Waterford Foundation was formed, one of the organization's paramount objectives was to buy the Mill. The month after the Foundation was incorporated, the owner was asked what he wanted for it, with or without machinery. In August, 1944, the Board of Directors empowered D. M. Myers to purchase the Mill for a price not to exceed $2,000, and by November, he had done so.

A committee was immediately appointed to consider the utilization, protection, and repair of the Mill. Ardent advocates of putting the Mill back into operation and producing water-ground meals cried for the committee to consider this possibility. But the first decision the committee made was to recommend that the frame and metal storage end of the building be tom down and sold for scrap. The Board of Directors awarded the contract to Max Davis, at that time Loudoun County's outstanding (and only) junk man, and by July, 1945, his men had gotten to work.

Meanwhile, the Board had become enthusiastic about getting the building in good enough shape to open it during the annual exhibit in the fall of 1945. But these plans went awry when Davis' men bogged down on the demolition job, and Meloy Fishback, the contractor who had been hired to replace the weak flooring on the first floor, discovered that lumber would not be available (Lumber was scarce because of heavy demands during World War II). Sadly it was agreed that the Mill could not be ready in 1945, and solemn pledges were made to have repairs completed in time for the 1946 exhibit. But problems in getting the work done continued. By the end of 1945, the Board gave up on Max Davis and sold the back end of the building for $300 to Howard Thomas, on the condition that he take it down and haul it away. And after repeated attempts to obtain kiln dried lumber, the Board decided to patch and strengthen the existing flooring. The frustrations of the group were great. At last, in the spring of 1946, both contractors made their appearance and substantial work was accomplished. But as each Board member came up with another bright idea (spray painting the exterior masonry), or uncovered something that just had to be done (installing fluorescent lighting!), many more repairs were made than had been originally planned. Furthermore, work was deferred while the Mill committee deliberated on what interior changes would have to be made if it was decided to use the first floor as a tea room. Finally, when the work was completed in April, Mr. Fishback, whose patience, no doubt, had been tried for months, announced that he would do no more work on the mill, since changes were constantly being made in the plans.Undeterred, the Board continued generating idea after idea about things to do with, for, and to the Mill. Fenton Fadeley was appointed chairman of a new committee to plan the use of the mill. (Faint voices were still heard crying for the operation of the Mill as a mill.)

The Mill committee decided that the floors were safe enough to open the building that fall, and Mr. Fishback was persuaded to return and make essential repairs at a cost of $400.The debut of the Mill in 1946 was a huge success, and so delighted were the Directors with the results that they bubbled over with ideas about opening the building for the sale of handicrafts on weekends during good weather, and (once again) serving tea to visitors. Since the revival of early handicrafts was one of the primary objectives of the Foundation, it was decided to use the mill for craft classes, and by 1947, the mill was the scene of regular classes in rug hooking and braiding, wood working, tole painting, and lamps shade making.

In 1948, the question was raised of whether the south wall was settling because of stagnant water standing around the foundation near the old mill wheel. As recorded in the January, 1948, minutes, "the possibility of removing the old mill wheel was brought up, whereupon the meeting was hastily adjourned." The advocates of operating the mill as a mill were still making their views felt.

Intense discussion about the safety of the building took place at the February meeting, when Paul Rogers, counsel to the Board, reported that he had consulted an eminent engineer, who had found the building unsafe for any use. The expert said, "there is a definite movement from month to month, caused by the north wall pushing to the south and forcing the south wall steadily outward; the force comes from the top more than from the foundation, and it will become progressively worse until one day the entire structure will over-balance and then even the vibration of a truck going by could bring it to the ground." Panic! However, Allen McDaniel, the president of the Foundation, reported that he had some time before installed wires to measure the actual deflection of the building, and had discovered a six inch deflection southward from the top story, three inches on the second floor, and practically none on the first floor. He thought stagnant water in the mill race could be causing sinking of the foundation, and engineers he had consulted felt that the building could be made secure by filling in the mill race. (Farewell to the dreams of reopening the mill as a real grist mill).

The Board agreed to seek more extensive engineering opinions, and several weeks later another consultant reassured the Board that there was nothing to indicate that the building was collapsing. The building had been checked weekly and no further deflection or the slightest evidence of movement had been found. The Structural Clay Products Institute made a study of the building, and presented three alternatives for its strengthening. The Board favored a plan which contemplated the removal of the roof at the third floor level (horrors!) but it was decided to defer any repairs until a complete restoration job could be accomplished. Since the cost of this was estimated to be $7500, and the still struggling Foundation had only about $1100 available, these grandiose plans were shelved for the nonce.

But not for long. So many complaints were received about the Mill not being open during the 1948 exhibit, that the Mill committee decided to repair the first floor and block off the upstairs and the platform. Meanwhile, the Board decided to repair the top two stories without changing the building. Pending complete restoration, tie rods were to be installed on the top floor to strengthen the entire structure.

Spring of 1949 saw the Mill a beehive of activity. Mr. Fishback, eating his words, was back again, installing the tie rods, removing the old flooring on the first floor, leveling the joists, and laying new flooring. The Board, now more conscious of the need to preserve all they could, agreed to move, but stoutly opposed removal of the old burr at the foot of the stairs, even if it interfered with laying the new floor or access to the staircase (and it is still there today.)

But, alas, all was not yet perfect. In June, Mr. Fadeley vividly described the dreadful problems he had encountered in attempting to remove the pool of stagnant water under the mill wheel. With great difficulty equipment had been brought in at the bridge, the mill race and the area beneath the mill wheel cleaned out, and the upper part of the race filled with earth. Whereupon the entire basement of the mill filled with water. The Hamilton Fire Department was called to pump it out, but in 24 hours the basement was full again. It became apparent that there was a spring under the mill wheel (which any mill builder or operator would have known, since that is one of the characteristics of a good mill site). The spring had been opened by the cleaning and a strong stream of water had been released, with no outlet except the mill basement. Frantically, the dirt was dug out again and pipe laid from the spring down the race and away from the mill foundation. The problem was solved, and there was now a source which could supply a mill with water whenever the Foundation could afford to put plumbing in.

In 1955, ex- President McDaniel reported that his measurements showed no change in the deflection of the mill walls since the dire days of 1948, when imminent collapse was predicted.

Comparative quiet and tranquility descended on the mill in the ensuing years. The building, clearly stable, was used for the crafts exhibits, classes were held regularly, and for a while the building was open for sales and, yes, for tea during the summer. From time to time the question arises of reactivating the mill wheel, cleaning out the mill race, etc. But the expense of repairing the dam and restoring the mill and mill race has always far exceeded the resources of the organization, and the idea is always reluctantly abandoned.

In 1975, to ensure its protection, the Foundation gave a preservation easement on the mill to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.The building has been used to display traditional 18th and 19th-century crafts during the annual Homes Tour and Crafts Exhibit for the past 55 years.

Copyright © Waterford Foundation

xwx